Littoral

Introduction

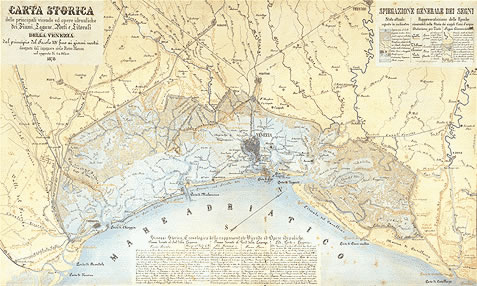

It is the area of the Lido facing the sea. The "Lidi"

are strips of land separating the lagoon from the sea and stretching for

about 50 km: from the mouth of the Brenta to that of the Sile (From "I

litorali sabbiosi del lungomare veneziano -part 2").

They are formed by a belt of high dunes made up of alluvial materials

deposited mainly by two rivers: the Tagliamento and the Piave. The current,

which in the Northern Adriatic Sea has a direction from northeast to southwest,

has made these alluvial deposits parallel to the coast.

6000 years ago this zone used to belong to Veneto's plain and successively,

with the rising of the sea level (eustacy)

and the lowering of the soil (subsidence),

it gave rise to longshore bars. Veneto's old plain, which, until 18.000

years ago reached the city of Pescara (from "La Laguna: Origine ed

Evoluzione" in "La Laguna di Venezia") is made up of "caranto",

a layer of very compact mineralised clay which forms the natural bed of

the lagoon. On this lagoon bed the Venetians have set the stakes that

support the buildings of the city.

The wide marshland, which had been confined behind that line, was initially

a fresh water lagoon, but periodic breakthroughs of the tide let sea water

enter, turning it into a brackish water lagoon (from "Guida alla

natura nella laguna di Venezia - Itinerari, storia e informazioni naturalistiche",

1996).

These processes are still active and littorals are continuously involved

by constructive phenomena as the deposit of sandy material coming from

the sea (sedimentation)

and by destructive phenomena as marine and eolian erosion.

The aspect of the littorals has changed during the centuries not only

because of the natural evolution of this extremely dynamic environment,

but also because of continuous human intervention, as in the case of the

building of the "Murazzi", in the deflection of the tributaries

from the Lagoon, and successively in the realisation of jetties and groynes.

Human Interventions

Man's relationship with the lagoon has been constantly characterised

by interventions which began right from the time of the first settlings

in this environment.

Until the 15th century interventions were restricted to a limited number

of works of consolidation and embankment that did not modify the essential

characteristics of the original lagoon.

Major works which influenced and started to modify the natural dynamisms

began from the 18th century.

The first interventions date back to 1738, when the Republic of Venice

realised along the littorals of Malamocco, Pellestrina and Sottomarina

the so-called "Murazzi": sea defensive works made up of Istrian

stone and "pozzolana".

They are jetties whose aim was to create a barrier to prevent the sea

from attacking and eroding the banks.

The idea of building these defensive works was conceived in 1716 by Father

Vincenzo Coronelli. He sent the "Savi ed Esecutori alle Acque",

main office in charge of civilian public works, his innovative project,

in which he proposed to substitute the traditional sea defensive works

made up of oak trunks and filling material with a real staircase made

up of Istrian stone blocks.

But it was the Water, Rivers, and Lagoon supervisor Bernardino Zendrini

who carried out this project thanks to the employ of "pozzolana",

a recently discovered material, which solidifies when it is mixed to lime

and if it comes in touch with water. This way the Istrian stone blocks

"welded" with each other and made the "Murazzi" barrier

even more effective.

ne more intervention that modified the aspect and the dynamisms of the

lagoon was the deflection

of the lagoon tributaries. Because of the sediments coming

from the tributaries, which were not compensated by the erosive effect

of the sea currents, the natural evolution of the lagoon environment would

have meant its silting up.

The "Serenissima Republic" has always regarded the silting up

of the lagoon as a problem because of the negative effect it could have

had on the city of Venice, whose safety and prosperity were indissolubly

linked to the existence of the lagoon around the city.

The first interventions on water-courses were first performed in the 12th

century: the plain water-courses were embanked in order to limit the erosion

and the consequent transport of sediments to the lagoon. These works did

not bring the expected results and it was therefore decided to face the

problem radically deflecting the rivers that flew into the lagoon.

The first river to be deflected was the Brenta, whose course was moved

from Fusina to the sea in 1548. The silting up of the Lagoon was actually

slowed down, but at the same time both the erosion and the withdrawing

of the salt-marshes increased, a problem that has been discussed since

1600.

In the Lagoon there is still a well visible track of the old course of

the Brenta: the Grand Canal, an old lagoon tract of that river.

In 1896 the Brenta, because of the difficult downflow and the consequent

flooding caused by the winding course it was forced to follow to reach

the sea, was newly deviated in the Lagoon. However, in the following 40

years the increase in the silting process led to the definite decision

to deflect the river to the sea, in the bed of the Bacchiglione.

The Piave did not have such a troubled history as the Brenta had: it was

first deflected to Cortellazzo, then to Santa Margherita, but in 1862

it flooded and went back to hold the river bed that leads to Cortellazzo.

The Sile, being a resurgence river, has always

presented few problems of sediment transport and was deflected in 1680

in Piave's old river bed mainly for health problems.

The deflection of the tributaries to the sea caused the disappearance

of the marsh belt, which formed a peculiar and important avifauna environment

and to an increase in the level of the salinity

of the salt marshes and of the lagoon beds.

Freshwater environments are currently reduced to small portions in the

lagoon edge area and they are sometimes formed by artificial environments

as deserted clay mines later transformed into in marshlands (e.g. Cave

Gaggio).

During the 19th century interventions were carried out on fish farms building

fixed frame embankments and jetties: these modifications started a process

of substitution of lagoon environments with land environment. (From "

Le problematiche naturalistiche nella progettazione e gestione degli interventi

sulla Laguna”, 1997).

The jetties are hundreds of metres long and link the sea to the Lagoon

allowing the ebb and flow of the tide.

They were built during three subsequent phases starting from 1805 at the

Lagoon inlets of Malamocco, Lido and Chioggia in order to deepen the seabeds

hindering the natural silting up of the canals and in order to allow big

tonnage ships to enter the port of Venice.

By the narrowing of the section of the canals, the entrance speed of the

current increased and so did the eroding force acting on the beds, whose

depth indeed changed from the original 5-6 metres to the current 20 even

30 metres . This modified environment changed the natural current circultation

causing downstreman at each jetty a loss in the sandy material and upstream

an accumulation of the same material, as it can easily be observed comparing

San Nicolò's littorals at the Lido and the littorals of Punta Sabbioni

at the Cavallino.

Natural evolution

From what has been said so far it can be easily understood that littoral

environment is continuously evolving both from a morphological and a functional

point of view.

Besides the changes that have been taking place on wide spatial scales,

one can also notice the continuous evolution characterising the littoral

environment.

sea current in the shape of heaps of algae

and dead

phanerogamae, enable the vegetal and animal population to evolve

and settle in an environment which apprently seems so inhospitable and

without resources (from “Un ambiente naturale unico – Le spiagge

e le dune della penisola del Cavallino”, 1992).

Each vegetal and animal "presence" helps to create the right

environment for the settling of other organisms in a dynamic process of

close relations that takes place in a restricted belt stretching from

the seashore to the littoral wood.

The organisms living in this environment had to adapt to difficult life

conditions, adopting some devices enabling them to survive.

Some plants as the Russian thistle (Salsola

kali), try to reduce as much as possible potential water

losses due to transpiration by reducing the leaf surface exposed to sunbeams:

this way they can accumulate water in the tissues and employ it in case

of drought (From "Un ambiente naturale unico – Le spiagge e

le dune della penisola del Cavallino").

The plants in this environment have succulent

leaves to reduce the loss of water due to evaporation, a quick vital cycle

to exploit as much as possible the most favourable periods and an elevated

seed production to enable at least some individuals to take root (From

"Un ambiente naturale unico – Le spiagge e le dune della penisola

del Cavallino").

The plants suitable to live at some distance from the sea are grouped

in strips parallel to the seashore line forming vegetal

associations whose characteristics reflect the variations

of the environmental characteristics from the seashore to the most inland

environments.

The first plants that can be met moving away from the seawater are the

so-called "pioneer

plants", that means that they are the first plants to

colonise an inhospitable environment and that they prepare the soil for

more exigent species.

The sand transported by the wind and the materials brought by sea currents

are deposited at the basis of these plants, thanks to which the first

belt of dunes is made up (From "Un ambiente naturale unico –

Le spiagge e le dune della penisola del Cavallino").

|